Chapter 19

The Heroine Sisters

1780 to 1788

“The Nine Armies War”: Burma Invades

As the new king, Rama I (Lord Chakri), had expected, just after his coronation in 1785 the Burmese did again invade. This time they mustered a huge force estimated at some 144,000 men, split into nine armies. Seven armies attacked north and west Siam and for the first time, two armies attacked south into the peninsula. The first of these two southern forces, comprising some 6,000 men, crossed over the Tenasserim hills and captured Prachup Kiri Khan; they then headed south, capturing Chumporn and Chaiya before attacking Ligor. They were joined in this attack by yet another Malay rebel army from Pattani, Terengganu and Kelantan. The isolated and outnumbered viceroy of Ligor and most of the people in Ligor city fled to hide in the forests and are said to have established the town that today is Tha Sala. The Burmese and the Malay rebels captured Ligor, Phattalung and Songkla and carried off many prisoners as slaves and much loot.

The second southern force was a seaborne fleet of some 5,000 men under the Burmese General Yiwun, which sailed down the peninsular west coast from Burma. Tenasserim and the main western Siamese port of Mergui had fallen to the Burmese in 1767 when they had defeated Ayutthaya; this attack down the west coast therefore was probably aimed at stopping the flow of weapons from the west reaching Bangkok through Siam’s only remaining west coast ports of Takuapa, Phuket and Trang and also at opening a supply line to the Burmese army in Ligor. This Burmese fleet captured Ranong in December 1785, then moved south and took Takuapa. In those days, Takuapa sat further up the river than the more modern Thai administrative town that exists today. It was protected by a stone fort that still stands. But the people of Takuapa had adopted their normal defensive plan and fled into the jungle. The Burmese fleet then sailed on south to attack Bangkhli and Phuket.

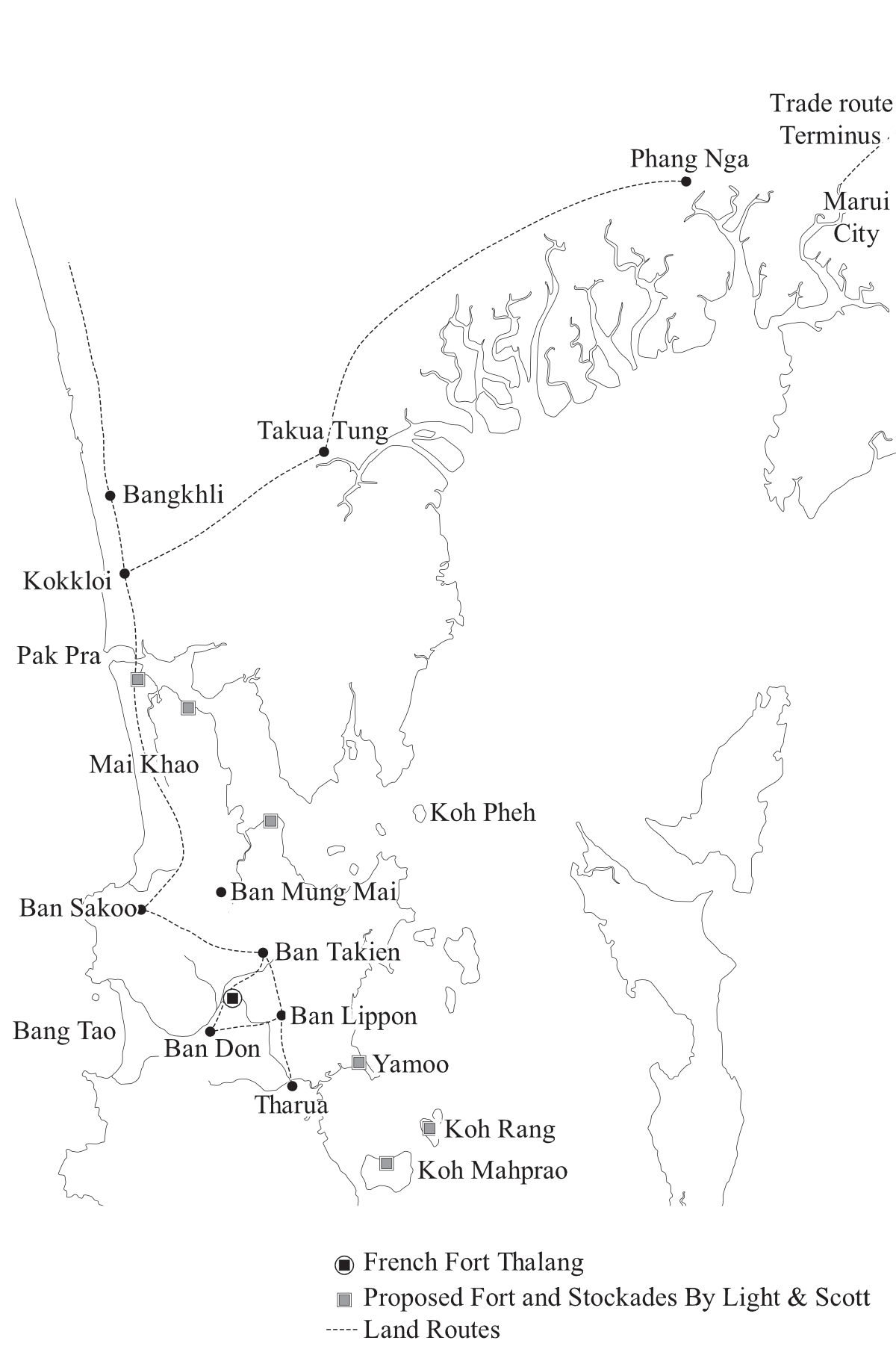

The two Siamese military commissioners in Kokkloi, Phraya Thammatrailok and Phraya Phiphithokhai, had only a small regular force of Siamese troops at their disposal and urgently ordered a militia draft of men from surrounding Phuket, Takuatung and Phang Nga. They decided to make a stand at Kokkloi junction where the jungle trails split, going north to Bangkhli, south to Phuket and east to Takuatung and Phang Nga. The Burmese fleet, with some 3,500 men, landed on Kokkloi beach, advanced inland and attacked the Siamese force fortified behind their bamboo stockades. The Siamese were routed and fled. Phraya Thammatrailok was probably killed in the engagement and Phraya Phiphithokhai, the remaining military commissioner, retreated with what was left of his force inland to the Kao Sok pass (near the Rajaprapat Dam) – presumably to try and hold this main pass to the east coast. This move, however, left Phuket and Phang Nga completely exposed and the Burmese victors moved south against Phuket. Captain Francis Light, the English merchant captain living in Phuket at the time, recorded that this invasion force consisted of “3,000 of the Burmar army in 80 large prows.” He noted this as he left Phuket on his trade ship for India. James Scott, a Scottish trader who also lived on Phuket at this time and also fled Phuket on his ship noted in his ship’s log for February 8, 1786, as he sailed away, that he sighted the van of this Burmese war fleet approaching Phuket.

Lady Chan and Phaya Pimon

On Phuket the people were leaderless as the governor of the island, Phaya Pimon, had died just a month earlier and no successor had yet been appointed. His widow, Lady Chan, was about 45 years old. She had been born around 1740 to Chom Rang, head of the hereditary family of Ban Takien and a former governor of Thalang. Her mother Mah-sia, we are told, was a well-to-do Muslim from Keddah who had come to Phuket in disgust after she was widowed and her younger brother had then stolen her estate. Chom Rang and Mah-sia had five children together on Phuket – two boys and three girls – all of whom, it is presumed, were Muslims. Lady Chan was the eldest daughter and was followed by her sister Mook.

Early in her youth Lady Chan had married Mom Si Phakdi, an official from Takuatung in Phang Nga. She had one daughter with him who had died of disease as a child in 1762. She had also had a son named Thian. When Lady Chan was around 30 years old, she divorced and then married Phaya Pimon, who at the time was governor of Chumporn. Around 1775, about ten years before the Burmese attack on Phuket, Phaya Pimon had been appointed as governor of Thalang under King Taksin’s new rule. Phaya Phimon was an outsider in Phuket but his marriage to Lady Chan had brought him local credibility and connections on the island. James Scott, a Scottish resident on Phuket at the time, noted, “Pia Pimon derives his local influence from his wife’s family.” In those days, the husband usually moved into the wife’s family house on marrying. In this case Phaya Pimon resided in Ban Takien with Lady Chan’s family. This in effect made Lady Chan the first lady of Phuket.

As governor, we are told, Phaya Pimon had kept a house for business in Tharua port, probably by the old governor’s house that stands in ruins in the Phuket History Park in Thalang today. However the couple reportedly used Lady Chan’s country house in Ban Takien as their main residence. In 1784, the year before the Burmese invasion, the visiting Scottish sea captain Thomas Forrest had visited the governor’s country house “on some commercial business.” He was accompanied by a fellow Scot, the Tharua resident James Scott. Forrest recorded that from Tharua to Ban Takien (just east of Thalang town today), the two men and their guards traveled:

on an elephant through a path worn like a gutter ... by the elephants feet and so narrow as not to be above an inch or two wider than his hoof. I wondered how the huge animal got along. About two miles from Tharua we got into open country again full of rice fields, well watered yet not swampy. In about three hours we reached the governors house which is more commodious than the one at Tarua.

Forrest tells us that Lady Chan’s country house was:

“built as all their houses are, of timber and covered with palm leaves, an universal covering in Malay countries. In his garden we found limes oranges and pummel noses [pomelos]. The governor gave us a very good dinner but did not eat with us. He did not speak Malay but had a linguist who spoke Portuguese. After dinner we were entertained with three musicians who played on such string instruments as the Chinese play on at Canton. Having drank teas we took our leave.”

Phaya Phimon, already in his seventies, fell very ill shortly after this visit and died in December 1785, just before the Burmese invasion of the island so the Phuket locals now looked to his wife, Lady Chan, for leadership.

Lady Chan Resolves to Fight

The Thai Annals of Thalang report that Lady Chan was in Kokkloi with the Siamese military commissioners when the Burmese attacked there. Maybe she had gone there with the Thalang militia the commissioners had requested, however Phuket lore, according to the local re-enactment theatre they put on each year, says she had just been arrested by the military governors as she and her husband had been late with tax payments due to the crown.5 After the Thai defeat in Kokkloi Lady Chan fled back to Thalang with the remnants of the Phuket militia. She later wrote to Captain Francis Light:

“When the Burmese came, Phaya Thammatrailok [the commissioner] summoned me to Pak Pra. I returned home when they captured Pak Pra. Those who guarded the place had gone away and left it and everything had been looted ... when the Burmese defeated the [Siamese] at Pak Pra, (Kokkloi) the people became scared and fled into the jungle leaving their homes and properties which were later seized.”

When Lady Chan returned to Thalang the people of Phuket may have heard that Ligor had fallen to the Burmese and also the rumor, spread by the Burmese, that Bangkok had also fallen to them. The people on Phuket therefore had no idea if any Siamese force might be coming to their rescue. A meeting was called to decide whether they should all attempt to flee to Phang Nga and the jungle or attempt to make a stand at the fort at Ban Don built by René Charbonneau almost a hundred years earlier. At this time, Captain Light estimated that Phuket had a population of around 14,000 souls, of whom only around 2,000 were able fighting men and of these, only a few hundred were professional fighters. Most of these were the former retainers of Phaya Phimon, who now followed Lady Chan. She apparently took good care of them so as to keep them loyal, as we see from another letter she sent to Captain Light in Keddah. “The men sent to guard the town and the fort are short of opium. Please have Captain Sakat [Scott] bring up nine or ten Thaen [a measure of opium].” The rest of Phuket’s militia were a motley mix of traders, fishermen, farmers and miners.

So whilst deciding to stand and fight was not a great option, fleeing was also hard, as the Burmese were already on the mainland opposite and their war prows were scouting all around the island to intercept fleeing boats or swimmers (to keep or sell as slaves). Supported by her younger sister Mook, Lady Chan took the brave decision to make a stand at the Thalang fort. Since the Burmese had captured Mergui almost 20 years before, Phuket had become Siam’s main western port for arms importation from India and the West. So, in her favor, Lady Chan knew the fort had many cannons and the island was well stocked with powder, grapeshot and muskets. Victuals, arms and valuables were hurriedly taken to the fort and any remaining food sources outside the fort were destroyed to prevent the Burmese from getting them. We are told that about 600 Phuketians, men women and children, crowded into the fort.

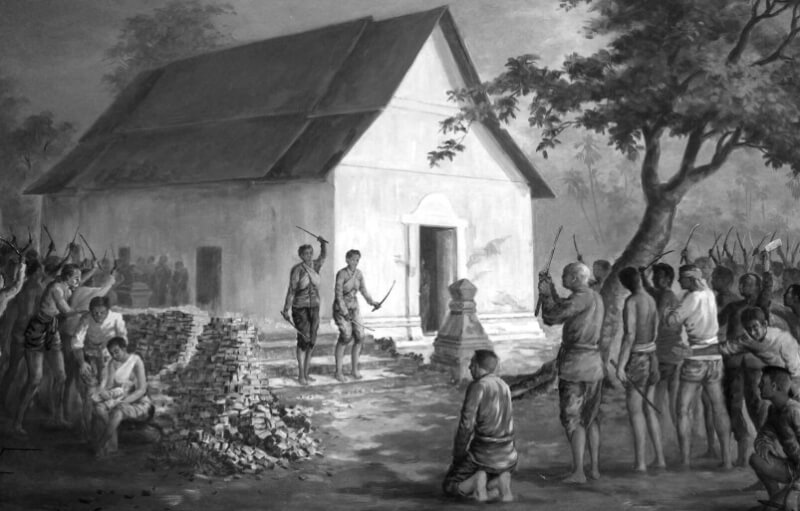

19.1. A painting of Lady Chan and her sister exhorting the people of Thalang not to flee but to take a stand and fight the Burmese invaders.

The Thalang Fort Holds Out

The Burmese fleet landed at Nai Yang beach in northwest Phuket and captured Ban Sakhu, the town just south of the airport. Others paddled their war prows inland to Thalang up the klong (river) that flows down from Thalang and empties into the sea at Layan beach north of Bang Tao, and to this day this klong is still known by many locals as “Burmese soldier Klong.” The deserted villages of Ban Sakhu, Ban Takien, Ban Lippon and Tharua were sacked and then burnt by the Burmese invaders who then converged on the Thalang fort, which stood somewhere between Thalang and Ban Don.

The Burmese troops on Phuket probably numbered fewer than 3,000 men. They had no large siege cannons, just the small-caliber demi-culverins and swivel cannons they took from some of their war prows and remounted on wooden platforms. These were not suf- ficient to bring down the earthen and wooden walls of the Thalang fort. Nor could they outrange the bigger Danish and British field cannon in the fort. Some of the Burmese troops had muskets and bayonets but most would have carried only spears and swords. The Burmese army surrounded the Thalang fort, but stayed out of range of the fort’s cannons. There they dug trenches and built stockades in preparation for a siege of the fort.

Lady Chan apparently attempted to bluff the Burmese as to the strength of her forces by having the women in the fort made up to look like soldiers. This was not difficult at that time as Siamese men and women, as we have seen, wore similar clothes and hairstyles. Some 50 years after the siege of Thalang John Anderson, an EIC government official in Penang, recorded (though perhaps rather simplistically) how Lady Chan had done this:

“The wife of Pia Pimone, the former Siamese governor of the island, was in the habit of relating to her visitors, with particular satisfaction, a strategem for intimidating the Burmahs ... when they had effected a landing and attempted a night attack. A small fort had been constructed, with a door in front and one in the rear. Having but few muskets, the old lady caused the leaves of coconuts [palm fronds] to be stripped and cut to the length of a musket and made all her attendants throw one across each shoulder. They then paraded round and round the fort, entering at one door and going out the other, thus giving the appearance of a large assemblage of troops entering the fort, as if they had come from a distance. The Burmahs, seeing so many men parading about became alarmed ... and took off to their vessels.”

The Thai Annals give us a more heroic version of the siege, telling us that the Phuketians

“assembled men and built two large stockades wherewith to protect the town. The Dowager governess [Lady Chan] and her maiden sister displayed great bravery and fearlessly faced the enemy. They urged the officials and the people both males and females to fire the ordinance and muskets and led them day after day in sorties out of the stockades to fight the Burmese. So the latter were unable to reduce the town and after a month’s vain attempts, provisions failing them, they had to withdraw.”

The Burmese siege of the Thalang fort lasted 25 days and involved some heavy day and night fighting. The new governor of Thalang appointed shortly after the Burmese invasion recorded that “The Burmese suffered between 300 and 400 casualties, killed and wounded. They then broke off the action and retired.”

Phuket historical lore today likes to tell us that the Burmese in Phuket left because of the indomitable leadership of Lady Chan, her sister Mook and the stout defense by the Phuketians. This may well be so, but a more cogent reason was probably the inspirational and decisive generalship of Rama I. In the north, he had rapidly defeated the main Burmese military thrust at Bangkok. He then equally rapidly dispatched an army down the peninsula to relieve the south. This army defeated the Burmese and Malay rebel force in Ligor and the eastern peninsula at a big battle just north of Chaiya. They then pursued the fleeing Burmese force back across the Tenasserim hills into Burma. The Burmese force in Phuket, on hearing about this defeat, probably realized that their main raison d’être – creating and holding a supply line to their eastern peninsular army – had disappeared. Therefore staying on Phuket served little purpose. They were hungry, outgunned by the cannons in the fort and had already sacked and burnt all the rest of Phuket. They had pillaged anything of any value and had captured hundreds of locals who were carried back to Burma as slaves. So there was little point in staying and on March 13, 1786, five weeks after they had first invaded Phuket the Burmese reportedly returned to their war prows and sailed back north up the coast to Burma.

By any standards, Rama I, one of Siam’s greatest generals, had won a brilliant victory. For her forthright leadership in the south, Rama I later awarded Lady Chan the title of Thao Thepkrassatri. Being a woman, she was unable to take over from her husband as governor; however, later on one of her sons became governor of Phuket. Her younger sister Mook was given the title Thao Srisoonthorn and Rama I requested one of her daughters as a concubine in his royal palace in Bangkok; she later bore him a child. In 1967 the Heroines Monument was built at Tharua on Phuket and the two main roads that meet there were named after the sisters, Thepkrassatri Road from Phuket Town and Srisoonthorn Road from Kamala.

A Bitter Victory

Today the so-called heroine sisters’ defense of Phuket is hailed as a great victory by the locals, but it most surely would not have seemed like that at the time. Although the Burmese had gone and some of the locals had kept their few valuables and avoided being killed or dragged off as slaves, that is about all the good that can be said of it. For a month the Burmese had occupied and utterly devastated the entire island outside the small confines of the walls of the wooden Thalang fort. No figures are known, but hundreds of locals probably died in the fighting and from food shortages and disease or drowning when trying to flee to the mainland. Probably several hundred if not a few thousand more were captured and carried back to Burma to become slaves. Most others had fled to the mainland and the island was depleted of people. All the villages, temples, homes, boats and crops had been pillaged, burnt, uprooted and destroyed by the Burmese scorched- earth tactics before they left and the real suffering and hardships – and many more deaths by starvation – were still to come. There was a shortage of food and people to work the fields or to dig for tin. Captain Light kept many of the letters written to him by the people of Phuket during this difficult period. They are now in a collection in London and give us a sense of the hardships following the Burmese invasion.

Lady Chan, for example, wrote to him shortly after the siege “Now I am destitute without anything ... because of the Burmese attacks on Thalang, the district is in confusion ... we are in great dearth of food ... the people of Thalang are starving from want of rice.”11 T’ha Prom, a nephew of Lady Chan, also wrote to Light, “This is to let you know that I am undergoing the most extreme degree of hardship and difficulty ... In the Burmese attack on Thalang many of my friends were lost to me, killed in the fighting.”12 Lady Chan again wrote to Light some months later, appealing for him to send up rice urgently from Keddah:

“At present the people of Takuathung and Bangkhli are scattered because of the destruction of their villages. The whole region here is in disorder. The Burmese burnt much rice and it is in very short supply; there is insufficient to provide for the people until rice is again available from the fields. Please think of [us] and have your captain bring up a trading ship with merchandise and rice so that the officials may be able to distribute enough for the people to go on cultivating their fields. ... I have organised the digging of tin in the forest and have obtained some which has been used to purchase all the rice available at a high price.”

The newly appointed governor of Thalang after the Burmese invasion also wrote to Light pleading for him to send food. “The people at Thalang are starving for want of rice. Out of your goodness have Captain Scott bring up two or three thousand gunnies [sacks] of rice for distribution to the people to save them from death.”14 Captain Light himself wrote to the EIC directors in Madras, telling them, “The people of Junksalong, after expelling the Burmese, are distressed by famine and expect another attack this season.”

In November 1786, a year after the invasion, Light also wrote to Madras to say that the sultan of Keddah had just been ordered by Rama I to prepare his fleet and army to defend Phuket against an expected new Burmese attack. Smaller-scale Burmese attacks and slave raids also continued up and down the west coast of Siam throughout the following years, keeping the distraught and starving people in the greatest fear.

So, with Phuket depopulated – its towns, business, agriculture and villages ruined and many of the locals dead, dissipated, enslaved, starving and fearful of another Burmese attack at any time – the great victory celebrated by the locals today would have seemed rather specious at the time. But a victory it was, compared with the horrors that Phuket would suffer when the Burmese invaded again 24 years later.

Map 8: Exisiting and Proposed Forti cations in Northern Phuket